How Not to Spot an Epidemic

Welcome to the first issue of Never Just Science! When I sketched out a plan for writing this newsletter, I thought I’d likely start with some obvious topics: What is scientism? Or maybe Richard Dawkins’s racist tirades? Or, what’s with the fly in the logo?

I’m pretty sure we’ll get to all of these things, eventually. But first, we’ve got to talk about coronavirus. Specifically, where the United States’ response to the outbreak falls on the spectrum of hapless-to-nefarious. In the past week, we’ve learned that:

Workers from the Department of Health and Human Services sent to assist Americans evacuated from Wuhan were not trained in infection control, were not issued protective gear, and were not tested for the virus (per the Washington Post)

The Department of Health and Human Services proposed quarantining Americans evacuated from the Diamond Princess cruise ship at a decommissioned army base with a poorly maintained runway and a hospital whose isolation rooms contained only training props, including painted-on light switches (yes, this detail is real, also per the Washington Post)

The CDC’s official test had a bad reagent (per Science and this terrific piece from ProPublica)

The US confirmed its first cases of community transmission and its first deaths from the novel virus (per everywhere)

It seems coronavirus has been circulating, undetected, in Washington state for at least six weeks (per lots of places, but once again, let’s go with the Post)

President Trump and his surrogates, meanwhile, have suggested that the virus is some sort of partisan conspiracy. In a measure that was (apparently?) intended to be calming, he also put noted not-a-public-health-genius Mike Pence in charge of coordinating the U.S. response. (If you’re not familiar with Pence’s prior track record failing to contain epidemics, I highly recommend the Indianapolis Star’s reporting on the devastating HIV outbreak in Scott County, Indiana.)

All of this raises the electric question of whether someone in the Trump administration actively suppressed public health agencies’ ability to detect the spread of the virus in the United States, and what such manipulation might mean for Americans’ willingness to listing to experts.

Now, it seems to me that at least some of how this is playing out in the United States is a direct result of this administration’s trademark brand of malevolent incompetence. I’d especially love to know more about why, exactly, the CDC developed its own (faulty) test instead of following the WHO’s existing guidelines, and why the FDA insisted that state health agencies only use the CDC test. Something’s not right here, and so far, the CDC and FDA are refusing to answer reporters’ questions on how these decisions were made.

That said, I refuse to believe (as of yet) that the entire scientific staff of the CDC is engaged in a political conspiracy. Surveillance-level testing of a population is challenging under the best of circumstances and, as of mid-January, public health officials thought, based on the best knowledge at hand, that the disease had not yet entered the United States. We’re still learning about coronavirus, but it is fairly clear that many cases are mild—maybe even asymptomatic—and that severe cases look a lot like a nasty case of flu. Symptoms include a fever of over 100 degrees Fahrenheit, aches and chills, a dry cough and difficulty breathing, and potentially vomiting and diarrhea. It can easily progress to pneumonia or respiratory failure, particularly in older people and those with existing health conditions.

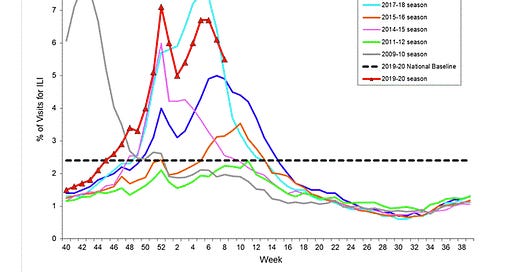

If you called your doctor with this list in mid-January, they likely would have told you to say home, drink lots of fluids, and take some Tylenol or ibuprofen to keep the fever down. We’ve all heard it: “Only come in if you’re having trouble breathing, if you stop passing urine, or if the fever lasts more than three days.” If you don’t go in, you don’t get tested, which means that you don’t have a confirmed case of anything and don’t end up in the CDC’s official statistics for flu or anything else. The percentage of people seeking medical care for flu-like symptoms is a little high this year, by the way—check out the CDC’s Weekly U.S. Influenza Surveillance Report for more details.

The first confirmed case of unknown origins in the United States started out with flu-like symptoms, but then got worse. It was only after the tests came back negative for known strains of influenza that the patient’s doctors began to wonder whether the person might have coronavirus. Here’s where things get tricky and sticky: Testing for coronavirus was delayed for nearly a week because the patient didn’t fit the diagnostic criteria. At the time, given the limited number of tests on hand, the CDC had confined testing to people who had recently traveled to China. The patient had not traveled to China; nor did the patient have immediate contact with anyone who had. Ergo, by the CDC’s logic, the patient couldn’t have coronavirus because the patient hadn’t been in contact with anyone who could have been harboring the virus. And unless and until this patient was tested, the United States wouldn’t have a confirmed case of unknown origin.

Now, of course, we know that we do have coronavirus in the United States. With more testing, the number of confirmed cases, both in the United Stats and around the world, will likely skyrocket. That doesn’t necessarily mean that we’re experiencing a pandemic; it just means that public health officials and medical professionals are only now testing for a disease that has likely been with us for longer than we knew.

Public health in the United States is underfunded. But maybe more to the point, accessing health care in the United States is notoriously complicated and expensive. For those of you who don’t live in the United States, here’s an example: I have high-deductible health insurance, which means that I’m out $200 to $500 any time I cross the threshold of my doctor’s office. A few years ago, when I insisted on getting an answer for why I had a lingering 103-degree fever and other disgusting symptoms, it cost me about $600 just to confirm that I had shigella. This earned me a call from a public health surveillance office, but no one could figure out how I got it, because I was the only confirmed case in the region. Most people who get shigella think they have run-of-the-mill food poisoning, and it takes a fairly motivated (or stubborn or sick) patient with the ability to pay to find out otherwise.

There’s a pattern here. We don’t know what we don’t look for (and we don’t know what we don’t know to look for). That’s true for any field, whether science, history, economics, or, in this case, public health. What we’re seeing here is a perfect storm of inherent epistemological uncertainty crossed with xenophobia (an obsession with “closed borders” and a “Chinese disease”) and nationalism (the CDC’s insistence on using its own, special [faulty] tests), in a country that lacks basic access to health care and paid sick leave. It’s not just one thing.

Wash your hands, folks. And fight for universal health care and paid time off.

Plus Ça Change: Tomorrow (March 4) is the 51st anniversary of a series of teach-ins and walk-outs protesting U.S. scientists’ relationship to the military-industrial complex. In the United States, many scientists think of March 4 as one of the high-water marks of scientists’ political activism. The reality was a little more complicated than that. I had much more to say about this, and how memories of March 4 relate to scientists’ contemporary activism, in Science last year.

Audra IRL: On Wednesday, March 11, I’ll be giving a book talk on Freedom’s Laboratory at the American Philosophical Society’s “Lunch at the Library” series in Philadelphia. Free, but please RSVP to Adrianna Link at alink@amphilsoc.org.

News You Can Use: Local stores out of hand sanitizer? According to The Oregonian, you can make your own by combining 2 parts isopropyl alcohol (that’s “rubbing alcohol” to Americans) with 1 part aloe vera gel. But better yet, wash your hands! And maybe your phone?